- By Deepali Nandwani

The Olympic Games have often been the catalyst for several cities to reconstruct and remodel into their modern versions, in keeping with the times. Barcelona transformed into a whole new city before the 1992 Games, so did London in 2011 and Tokyo in 1964. The buzzing capital of Japan is undergoing another round of ‘sustainable’ and technological metamorphosis for the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics.

The twenty-first century is proving to be a defining one for urban cities across the world, as they face challenges of extreme overpopulation, a huge need for infrastructure to cater to the number of people who are now calling cities their home, the changes brought by climate change and other sustainability issues. To deal with such humungous challenges, old cities will have to regenerate and renew themselves. Barcelona transformed into a whole new city before the 1992 Games, so did London in 2011, and Tokyo in 1964. And much like 1964, Japan’s capital city is undergoing urban renewal and makeover to deal with not just the 10 lakh people who are expected to pour in for the Games, but one that would sustain the city for the next two decades, if not more. Or, smart cities will have to be built from scratch, much like the Palava City by Lodha, spread across 4500 acres, which is designed to be among the world’s top 50 places to live in and offers a myriad of opportunities to work, learn and play.

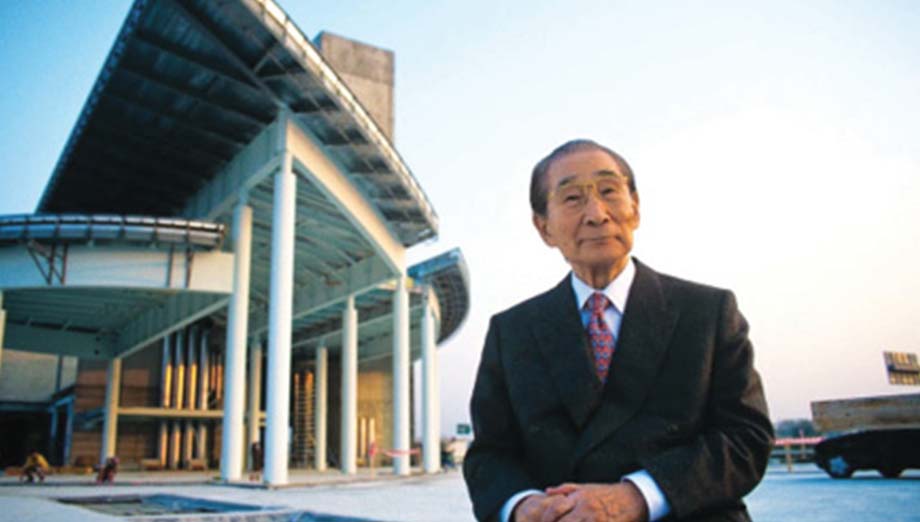

Tokyo is at the top of our list of world cities that are rejuvenating themselves on the foundations of sustainability, technology and modern urban planning. Home to 13.9 million people living in approximately 15,000sq.km area, which encompasses the Tama city on the western edge of the metropolis as well as the islands, it is constantly in a state of frenzy. The “metropolis of salaryman crowds” (as defined by the late architect Kenzõ Tange, winner of the Pritzker Prize for architecture), packed metro networks, neon-lit vertiginous towers and historic temples, is also a densely packed city.

Tokyo 2020 Olympics is the city's second tryst with the global sporting event for which a massive urban renewal project is currently underway. The New National Stadium is ready for the Summer Games.

And yet, architects and town planners refer to it as one of the most sustainable cities in the world. “Even though it lacks a marked central district, it is a patchwork of neighbourhoods with distinct identities: Ayoma with its fashion district and shops that look more like museums; the trendy hub of Harajuku; the temples and lively markets of Asakusa,” says Momoyo Kaijima, Principal Architect and founding-partner of Atelier Bow-Wow. The atelier curated Made in Tokyo: Architecture and Living, 1964/2020, on the transformations that Japan’s buzzing, heaving capital city underwent since the time it first hosted the Olympic Games in 1964. Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics will be its second tryst with the global sporting event.

The construction hustle in Tokyo right before the Olympic Games is laced by thoughts on how the city can be “made sustainable enough” to deal with issues of climate change and further urbanization. The city authorities will augment neighbourhoods such as Asakusa, Akihabara, Harajuku and Shibuya, which have distinctive architectural characteristics, into hubs for art and culture under the ‘Tokyo Vision’ plan. The organisers state that the Olympic and Paralympic will be “a catalyst for social change” and will help open up the city, known as much for people who tend to be reclusive and an ageing population, as for its fashion-forward culture. Masa Takaya, spokesman for Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics and its urban renewal programme says, “In 2011, earthquake and tsunami left some parts of the city devastated. The vision includes putting these areas right.” Takaya told The Guardian newspaper (London) that the Games will help authorities focus on the city’s softer legacy. “We are keen to leave an intangible legacy for future generations, who will enjoy a first-hand experience of the Games, for which a massive number of people from different backgrounds, cultures and languages will congregate.”

Tokyo’s city authorities and the Olympic-organizing committee are hoping that the 2020 Games will help them create a hydrogen-boost for its society by positioning the environmentally-friendly fuel as a new energy option.

Cool areas are being developed across Tokyo and the competition venues, with an agenda to lower Japan’s CO2 emissions. Architect Kengo Kum has designed the new National Stadium by blending steel and layers of latticed larch wood; the stadium is intended to “restore the link that Tokyo lost with nature” says Kum. The woodland-themed stadium, surrounded by trees and fresh verdure, will cost ¥156.9 billion ($1.4 billion) to construct and will stand at 47 meters (154 feet) so as to not mar the sight of the lush green of the outer gardens of the adjacent Meiji Shrine. A part of its roof is designed in the traditional architectural style of small slats made of wood, referred to as nokibisashi. An underground temperature control system, designed to encourage the growth of natural grass, has been incorporated into the building’s infrastructure, along with spray systems and air-circulating fans to alleviate the heat within. Eco-friendly accommodation for the Games will be converted into homes after; Wi-Fi spots beneath the venue seats and elsewhere will enable spectators to post messages and make videos.

Kum says Tokyo’s city authorities will introduce automated vehicles and automatic translation devices. “The Tokyo Olympics 2020 will showcase some of the world’s most futuristic technologies and modern sustainability efforts,” he discloses, which include battery-operated electric vehicles featuring automated driving, developed specifically to transport staff and athletes within the Olympic and Paralympic village. Panasonic has created motor-assisted power suits to allow people to carry heavy luggage with ease at the venues. Aruze Gaming’s Arisa, a sharply dressed six-foot robot, will guide people to toilets and lockers at the stadium, and offer directions and recommend tourist attractions in Japanese, English, Chinese and Korean languages.

Aruze Gaming's Arisa, a six-foot robot, will guide people to toilets and lockers at the stadium and recommend tourist attractions.

Tokyo’s city authorities and the Olympic-organizing committee are also hoping that the 2020 Games will help them create a hydrogen-boost for its society by positioning the environmentally-friendly fuel as a new energy option. Nearly 100% of all Tokyo’s metropolitan facilities will aim to use LED lights to reduce energy consumption. The main facility at the Athletes’ Village — the Village Plaza — is crafted from sustainably-sourced Japanese timber donated by local authorities around the country. After the 2020 Games, the Plaza will be dismantled and returned to the community, to be reused for benches or school buildings.

The authorities are constructing heat-blocking road surfaces that can reduce the temperature of the road by eight degrees across more than 100km of the city centre. “We have low-tech responses that have existed since the Edo period [1603-1868], such as water sprays,” Tokyo’s governor, Yuriko Koike, told The Guardian. Last year, in Japan, temperatures peaked at 42 degrees, leading the city to revive these ancient water sprays. Despite these rapid technology-and environment-inspired changes, some architects say that the 1964 transformation or the one before that, in 1961, was far more enduring. Architect Hiroshi Ota contends, “Tokyo 2020 is not daring enough compared to 1964, when buildings such as Kenzõ Tange’s Yoyogi gym were seen as design masterpieces.” As The Times newspaper wrote at the time: “The arenas have approached new heights of architectural imagination and efficiency. In the press room, journalists look over blankly over their typewriters at each other. They still feel stunned as they try to pay tribute.”

Tokyo’s city authorities and the Olympic-organizing committee are hoping that the 2020 Games will help them create a hydrogen-boost for its society by positioning the environmentally-friendly fuel as a new energy option.

Tokyo, incidentally, has been put through several transformations. The first attempt at rethinking urban planning happened right after World War-II, which had left Japan wounded by the losses. Dr Raffaele Pernice, architect, urban planner and educator at UNSW Sydney, who documented the first round of Tokyo transformation as a PhD candidate at Waseda University in the city, says, “Post World War II, between the 1950s and 1960s, Japan undertook large-scale urban planning and transformation projects. The idea was to create urban utopias ready for the economic miracle that the government had planned.

Architect Kenzõ Tange's work inspired several Metabolist architects in Tokyo, who created an intricate urban patina that is the city today.

It was a matter of national pride for the Japanese after WWII. It was also an attempt to foster industrial capitalism. The unprecedented phenomena of urbanism and the concentration of economic activities in the main cities of the archipelago, particularly in Tokyo, made them very complex and disordered beings. This disorder necessitated a balanced development of urban settlements during the post-war years.” In his documentation of post-war Japan, The Transformation of Tokyo during the 1950s and early 1960s, Dr Pernice writes about how young architects and designers developed new techniques for city planning. They modernised the shape and content of the city, giving birth to a prolific period of Japanese architecture.

Post-war Japan, destroyed by air raid bombings, faced crushing housing shortage (an estimated 4 million units were urgently needed), besides basic transport and industrial infrastructure that was left in shambles. The controls exerted by the US occupying administration, lack of basic material to reconstruct the cities, and economic collapse due to war limited the construction activity. People built wooden barracks across desolate fields of ashes in the burned cities, including Tokyo, to live in. But by 1950, the US had begun offering Japan aid, leading to large-scale economic growth.

The ancient water sprays, built in the Edo period (1603-1868), help cool down the city, where temperatures increasingly touch 42 degrees in summers.

Researcher Norman Glickman, who documented the rise of Japan during the 1950s and 1960s, wrote about how the migration of rural masses to cities led to a scarcity of land to improve housing and road infrastructure, resulting in congestion and chaos. Japanese architect Ken Tadashi Oshima, curator of Metabolism: The city of the future at Tokyo’s Mori Art Museum in 2011, says, “In the 1960s, a group of Japanese architects dreamed of future cities. The visions of Kurokawa Kisho, Kikutake Kiyonori, Maki Fumihiko, and other architects, who had come under the influence of Kenzõ, gave birth to an architectural movement that was called ‘Metabolism.’ Much like the biological concept by which it was inspired, they dreamed of cities that shared the ability of living organisms to keep transforming and responding to a changing society.

Kenzõ, clearly, was the man of the moment and his ideas have left indelible marks across Tokyo’s cityscape. Influenced by Le Corbusier, his works mirrored the aesthetics of Bauhaus architecture and the architectural legacy of Walter Gropius. Following the destruction of WWII, he was awarded first prize in a government-sponsored city planning competition to design the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. His axis-structured design centred on elevated buildings that negated all distractions. The Peace Boulevard, which stretches out to the preserved Atomic Bomb Dome, also features a moving cenotaph that lists the names of all who lost their lives. His other monumental works include the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building and St Mary’s Cathedral. He worked on creative, governmental and religious buildings while maintaining his distinct style that blended Bauhaus style with softer elements of design.

The Kengo Kum-designed New National Stadium blends steel and latticed larch wood in an attempt to restore the link that Tokyo lost with nature.

He inspired several Metabolist architects in Tokyo, who created an inspired urban patina that is the city today. But it was Kenzõ’s 1960 plan for Tokyo that transformed it at a time when most cities in the industrial world were experiencing urban sprawl. “Rather than expanding out, he aimed to restructure the city, using linear inter-locking loops spread out across the bay. Focusing on satellite cities, the design reflected his belief that the rising popularity of cars would be a game-changer,” says architect Tado Anto, a Pritzker Prize-winner himself. The second makeover that catapulted Tokyo into the league of the great world cities was for the 1964 Olympics, which acted as a trigger to facilitate the rapid improvement of infrastructure.

The temples and lively markets of Asakusa will be promoted under the Vision Tokyo programme to attract more travellers who seek out unique cultural experiences.

Kaijima contends that the city suffered from a shortage of functional infrastructure, including the lack of flush toilets. Most of the waste had to be vacuumed daily out of cesspits underneath buildings by ‘honeywagon’ (vacuum) trucks. But by the time the 1964 Summer Olympics came along, the city had put all that in the past. Quoting The Times correspondent from back then, “Out of the jungle of concrete mixers, mud and timber that has been Tokyo, the city has emerged, as from a chrysalis, to stand glitteringly ready for the Olympics,” citing a long list of buildings and accomplishments “all blurring into a neon haze, that will convince the new arrival he has come upon a mirage”.

The metamorphosis was not just surface: the authorities had laid out 100km of highways, constructed a new sewage system, and 21km of the monorail from the new international airport to downtown. The Tokaido Shinkansen bullet train blasted from Tokyo to Kyoto. Modern buildings such as the Tokyo metropolitan gymnasium, shaped like a flying saucer, added to the mirage vibe. Photographer David Goldblatt who captured the city at the time of the 1964 Olympics in his book The Games, termed it the single largest act of collectively reimagining Japan’s post-war history. If the 1960s reconstructions were to help revitalize a city left paralysed by war and large-scale immigration, Kum contends the current plan puts Tokyo on the vanguard of technology transformation and sustainable development.

The ancient water sprays, built in the Edo period [1603-1868], help cool down the city, where temperatures increasingly touch 42 degrees in summers.

The Kengo Kum-designed New National Stadium blends steel and latticed larch wood in an attempt to restore the link that Tokyo lost with nature; (Bottom) The temples and lively markets of Asakusa will be promoted under the Vision Tokyo programme to attract more travellers who seek out unique cultural experiences.

Panasonic has created motor-assisted power suits to allow people to carry heavy luggage with ease at the Games venues.